Misinformation about the pandemic is rampant. The internet has become a great source of health misinformation. Misinformation can spread like wildfire.

There’s information overload and people are having a difficult time separating fact from fiction. Is it possible to learn to debunk pandemic misinformation?

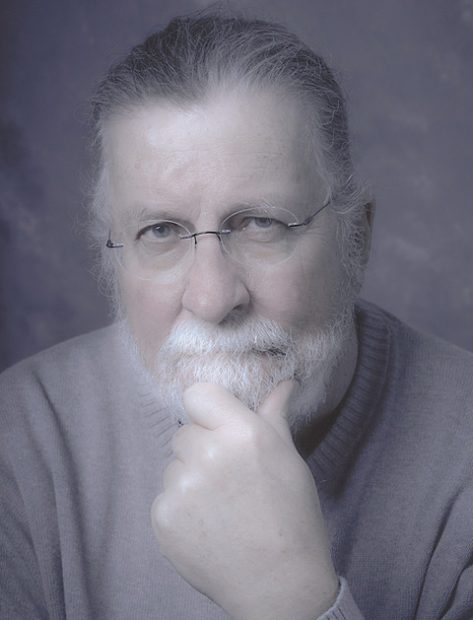

Gary Schwitzer, Publisher at HealthNewsReview.org and Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Minnesota School of Public Health, believes it’s possible to learn to debunk pandemic misinformation.

He helps journalists and consumers understand the importance of accurate and balanced news stories.

In an email interview — Mr. Schwitzer answers questions to help put things in perspective.

Q & A with Gary Schwitzwer

1.

Q:

Misinformation surrounding the coronavirus seems to be rampant, what can be done to counter misinformation?

A:

I have always believed that a strong grassroots movement to help the general public to improve their critical thinking about health care is required in order to counter misinformation. That is what I have tried to do on HealthNewsReview.org for the past 14 years.

But no one project, no one organization, can address all of the myriad misinformation that washes over the public every day like a tsunami.

So I believe we need to start from the bottom up to give people the tools to improve their own analytical skills, their own ability to weigh the veracity of claims, their own pathways for finding accurate, balanced and complete information.

2.

Q:

What can be done to empower consumers to be cautious and question what they read or hear?

A:

We need to instill in consumers what is often taught to journalists: If your mother tells you she loves you, check it out.

Consumers need to learn about rampant financial and intellectual conflicts of interest in health care, polluting many of the messages that reach the public. It’s not to scare them; it’s to educate them and to help them prepare themselves.

It is the reality of the marketplace and if consumers don’t know the landscape, they are more likely to fall prey to misinformation and the harms therein.

3.

Q:

What news organizations are getting it right when reporting on COVID-19?

A:

I worked in the South for 15 years and sometime during that period I learned the phrase, “The sun don’t shine on the same dog’s ass every day.” In other words, nobody’s perfect, nobody’s lucky, nobody gets it right all the time.

My 47 years in health care journalism has taught me that over and over. However, I’ve also seen the difference that one individual can make in any organization. Those individual efforts shine through on many days.

With those caveats, I would say that on most days I have been so impressed and grateful for the work of the New York Times, the Washington Post, ProPublica, Kaiser Health News, the PBS News Hour, The Atlantic, Vox.com, and the Columbia Journalism Review. I’ll stop there — emphasizing that this is an incomplete list only of the publications that come immediately to mind.

4.

Q:

Does debunking misinformation work?

A:

It depends on how you define or measure what works. Does it work to fact-check and debunk claims made by a President who lies regularly to the American public? It doesn’t seem to matter with his political base.

I know how I react to journalism that provides analysis that vets claims made by politicians, government officials, scientists, physicians and others. I am grateful for the analytical effort and for the education it provides.

In my sphere of influence of friends and family, I know that debunking efforts do work, they do educate, and they do reach an appreciative audience.

It is very difficult to measure the impact on the public of my HealthNewsReview.org project’s efforts over the past 14 years. While it is “only” anecdotal, there is a mountain of anecdotes of people writing me to say that we have helped them understand complex topics better than any other source.

So I have to believe that debunking misinformation works or I wouldn’t have stayed with this for 14 years.

5.

Q:

What’s the best way to share facts about the coronavirus with the general public?

A:

It can’t be done in a hurried manner. It shouldn’t be done in a rushed 300-word story. If a news organization can’t provide the time and the resources to put today’s events/announcements into context, with background and explanations and independent perspectives, it would be better off not reporting on the topic at all. Because to fail to do it correctly is to predictably cause harm.

It shouldn’t be done with single-source stories that may suffer from the inherent bias of one conflicted viewpoint — even from a well-known “expert.”

It shouldn’t be done without analyzing the limitations of the study or the announcement.

Not all studies are equal. There are flaws throughout the hierarchy of evidence. So to project certainty where certainty simply does not exist is wrong.

I could go on by pointing out the 10 standardized criteria that my team applied to the review of 3,200 news stories and PR news releases that included claims about health care interventions. But at a very high level, the three issues I just outlined — taking the time to do it right, interviewing independent sources with no conflicts of interest, and explaining the limitations — are essential.

6.

Q:

Who are top authoritative voices on the pandemic?

A:

I don’t feel comfortable naming “top authoritative voices on the pandemic” for some of the same reasons I answered #3 above with hesitation. In the face of so many uncertainties about COVID-19, how to treat it, and how to test for it, I think this is a time for humility on the part of anyone speaking to the public about the pandemic. It clearly is a time for scientists to talk as much about what they don’t know, what their uncertainties are, and what keeps them up at night — as they talk about what they think they know and think they have established.

However, having said all that, one of the people I think has done a terrific job educating the public is Michael Osterholm, PhD, of the University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP).

7.

Q:

What are the most trusted sources?

A:

See my cautious answers to #3 and #6 above.

8.

Q:

What are misleading key words that consumers need to be aware of when it comes to health news?

A:

20 years ago, when I was founding editor of the MayoClinic.com website (now defunct), I wrote an article, “The Seven Words You Shouldn’t Use in Medical News.” A somewhat-updated version is on my website. The important thing to emphasize is that I didn’t dream up the list; the words all came from patients I’d interviewed through the years. Those people told me that these words bothered them or were meaningless to them as they struggled with their illness. So I wrote:

I urge colleagues – both health care providers and professional communicators – to abandon their use for the sake of health consumers everywhere. I urge consumers of all health care information to be wary of these words because they mean different things to different audiences.

Gary Schwitzer

7 words to avoid in medical news:

Cure

Miracle

Breakthrough

Promising

Dramatic

Hope

Victim

You can read the reasons why sick people nominated those words for my list on my website.

Preprint

In the pandemic era, I would urge consumers to be wary whenever they hear a news story emanating from a preprint, which is a quick-to-publication online report that has not been thoroughly peer-reviewed.

A leading preprint website has a disclaimer on the top of its home page that states:

Caution: Preprints are preliminary reports of work that have not been certified by peer review. They should not be relied on to guide clinical practice or health-related behavior and should not be reported in news media as established information.

Gary Schwitzer

But some journalists, in the rush to beat the competition or to meet a daily story quota, go ahead and report information from preprints without warning readers or news consumers about the limitations of that information. This is not a new phenomenon, but in the race to answer questions about the pandemic, scientists are turning to preprints to communicate with their peers more often. And so journalists are perusing and reporting on preprints far more than at any time in the past.

Caveat emptor – let the consumer beware – if they’re not being told about the limitations of rushing to judgment based on preprint publication.

9.

Q:

What are your favorite sources for health news information?

A:

I listed some of them in #3 above. But I also learn a great deal from many who are effective communicators even with the limitations of Twitter. This includes not only clinician-scientists who somehow find time to comment on or explain complex topics on Twitter. But it also includes patients and patient advocates who bring their important expertise to online discussions.

I also appreciate organizations that are working hard every day to communicate with the public on pandemic topics, including:

— The Washington Post’s Coronavirus Updates Newsletter

— The New York Times Coronavirus Briefing newsletter

— NewsGuard and its COVID-19 Misinformation Resources

— University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy or CIDRAP

— Columbia Journalism Review — on many days during the pandemic and when it touches on coronavirus journalism issues.

I subscribe to CJR’s “The Media Today” daily newsletter for the most current perspectives. I’m quick to emphasize that this is an incomplete list because there are so many other organizations worthy of notice.

Follow Gary Schwitzer

Health information can be confusing…

30 Words

There’s an overload of health information. It can be confusing and difficult to decipher fact from fiction. Be empowered—Pause, question what you read or hear. Think like a journalist.

Barbara Ficarra–Healthin30